Day 59

BAM, saltwater!

After 59 days on the river, we finished our source-to-sea expedition on Sunday, September 28th, around 3 p.m. We are deeply grateful to the family and friends who made it possible for us to disappear into the woods for two months, and to come back again changed. This experience will stay with us for the rest of our lives.

To the river angels, strangers, and loved ones who offered resupplies, rest stops, and reminders of kindness along the way — thank you.

And to everyone who’s supported our fundraising goal for the fight against childhood hunger: we are proud to share that we’ve raised over $11,500 to date. Donations will remain open through Monday night — let’s see how far we can take it!

The remainder of this post will detail our final day and trip summary.

Final Day Log

1:15 AM- Arrived at Wax Lake Boat Ramp. There, we set up Leah’s tent and pretended we were “camping,” not “loitering next to a boat ramp.”

1:45 AM- I started trying to sleep. Leah actually did! It was so cold 😭

3:00 AM- Switched who was trying to sleep where.

Did we mention it was two adults and a puppy in a 1.5 person tent?!4:30 AM- Fishermen began their morning migration. Each spotted our kayaks, exclaimed “Oh, that’s a kayak!,” and then loudly debated whether we were awake. We were. At least one nearly jumped out of his skin when he realized there was a tent.

6:00 AM- Leah woke up and stared morosely at the mosquitoes attacking the tent, for those on the inside were laden with blood.

6:30 AM- Fully gave up on sleep, as Leah’s parents were arriving with breakfast. We tumbled out of the tiny tent to start our final day. They graciously took our unnecessary gear, allowing us to paddle the final day with nearly empty boats.

7:30 AM- Loading up and pushing off

8:00 AM- Actually paddling!

We followed the Wax Channel for about 9 miles, eventually turning into Wax Lake itself. Wax Lake is not a lake - at least not this time of year. It is more like the start of the bayou than a wide open space - it reminded me of some of the parts on the upper that were mapped as lakes but in reality there was only one path clear of the wild rice. I was initially worried about missing the turn to Hog Bayou (what if the rice blocked the path and we had to go back and find a different route through the lake?) but the clear path led straight into the bayou, so it was no big deal.

Hog Bayou is a windy path through the swamp with abundant vegetation (but not in a bad way), consistent flow, and dozens of alligators. It was some of my favorite paddling of the whole trip, with a quick but gentle current, lots of riverbends that were still wide enough for my boat to easily make, and plenty of interesting plants and animals to look at and listen to as we passed. Sydney felt misled, having expected something more akin to a cypress swamp than a slow moving river. She was also less than thrilled with the gators!

We turned the final corner, and there it was: BAM, saltwater!

We still had about a mile and a half of open water paddling after that to make it to Burns Point, where’d rejoin the real world, but we had done it. We were here! 2100 miles and change all led up to this - an easy paddle out a narrow bayou into the wide flat Gulf.

Trip Summary

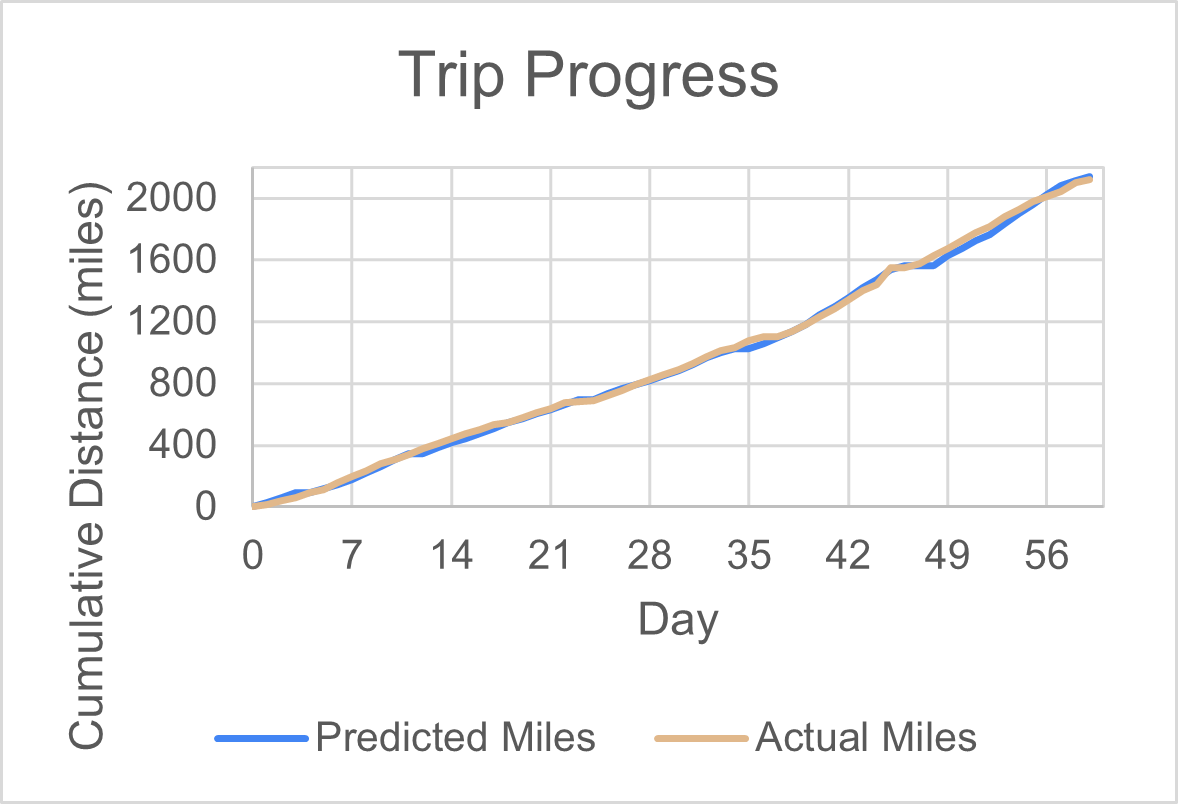

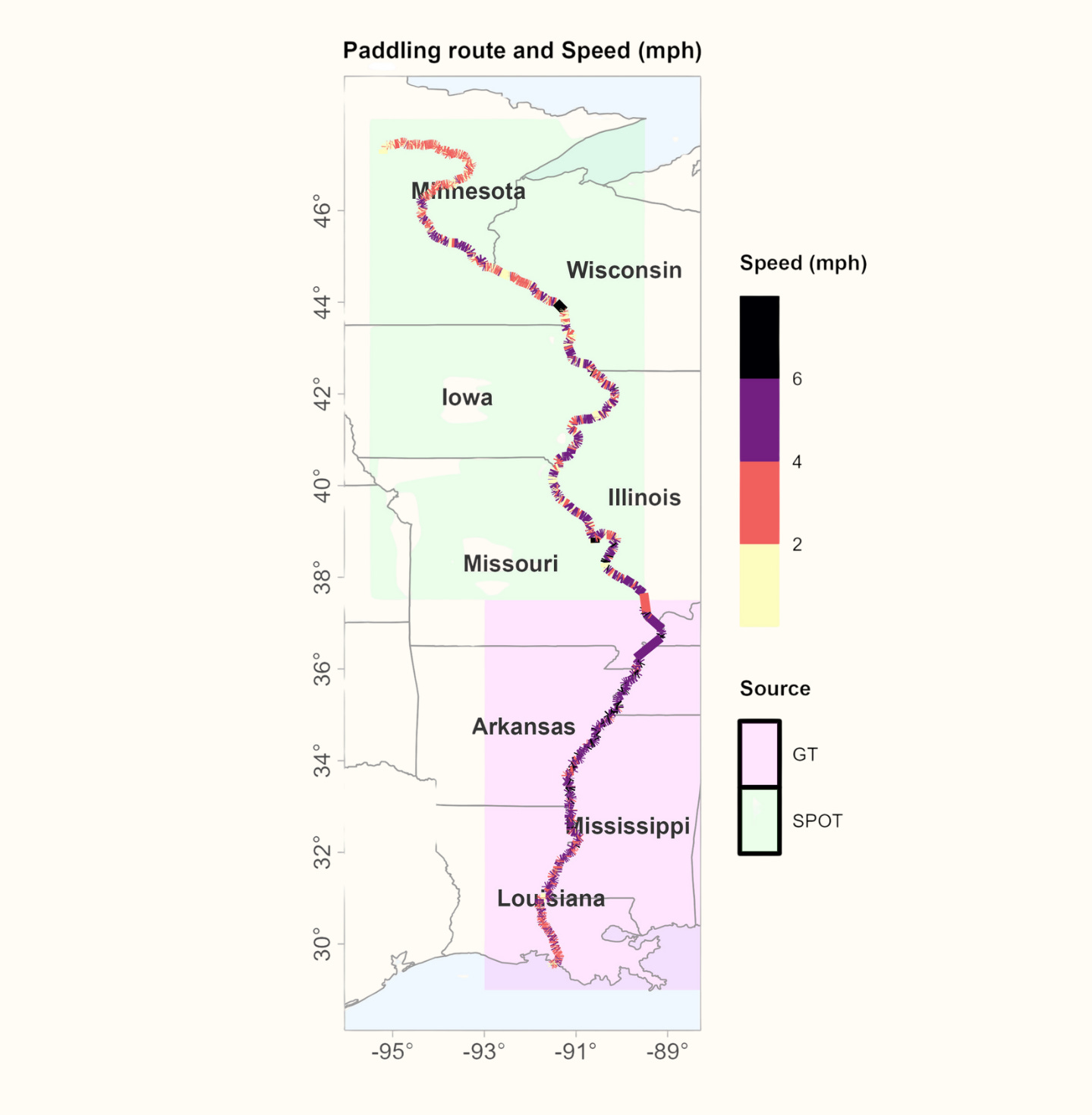

Total Distance: 2121 miles

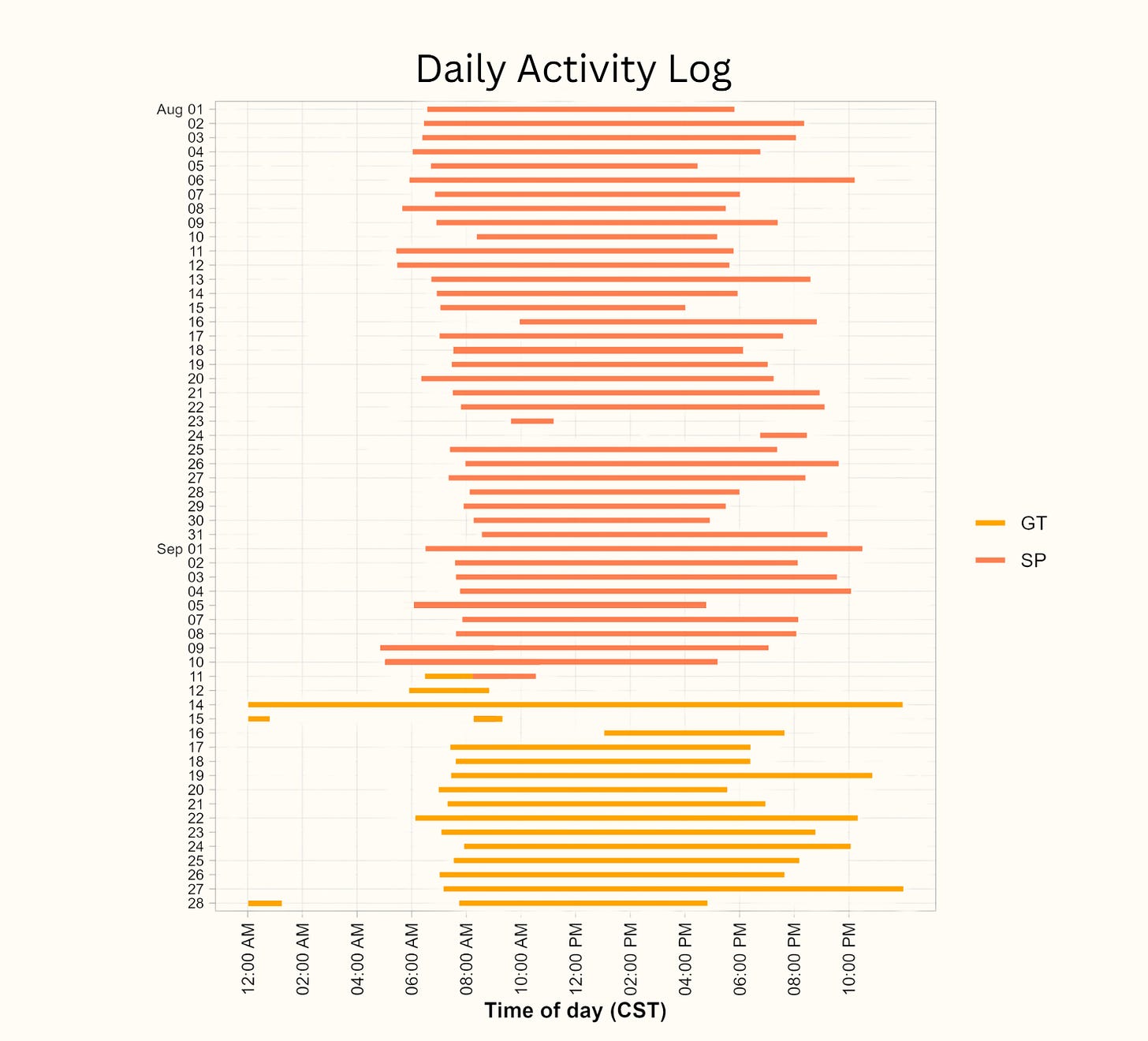

59 total days (1 zero day, 58 paddle days)

60 resupplies. This was counted in terms of separate stops, meaning if we refilled water, picked up a box of food, and went grocery shopping at the same stop, that’s 1 resupply, but if someone gives us a Coke from their boat, that’s also 1 resupply.

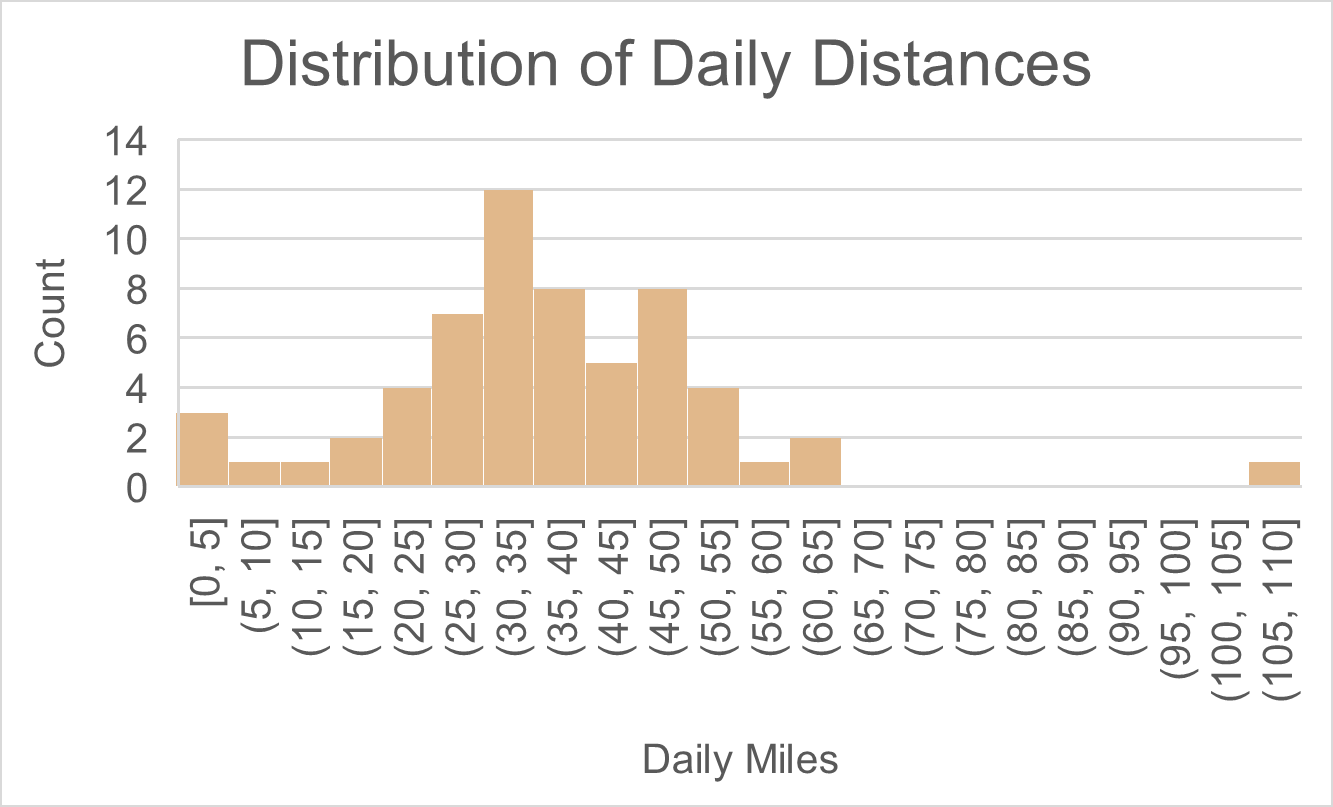

Ignoring outliers like zero days and 100 mile day, our mileage basically fell into 3 categories:

First 116 miles (first 5 days): 22 miles/day

Upper Mississippi River: 34.5 miles/day

South of Chain of Rocks: 46 miles/day

Overall average speed: 36 miles/day

Longest Day: 110 miles over 24 hours

Fastest Sustained Hourly Speed on 100 mile day was the last hour (11pm to midnight) at 6.57 mph. We credit this to the Christmas carols and it being the last hour.

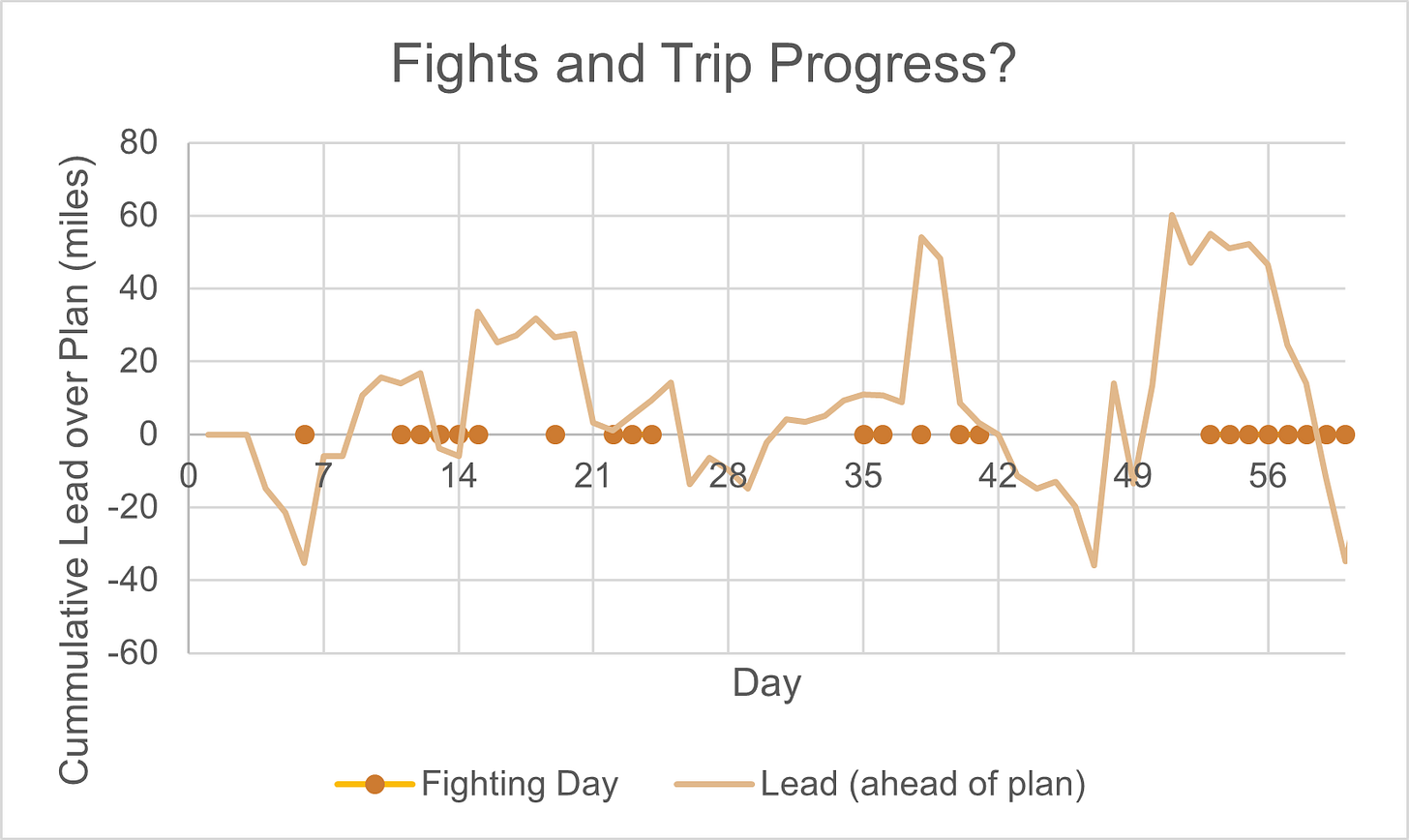

Furthest Deviation from the plan: 60 miles, meaning we were never more than a day’s paddle behind our planned schedule.

8 nights spent in a real bed. Thank you, thank you, thank you to the folks listed here:

2 in hotels (Memphis, Natchez)

6 with River Angels (Emma Bromenshenkel, Abby and Robbie Skiba, Jim & Ken, Deb & Dick Schroeder, Mike & Pat Porter, and Scott & Kristen Ladewig)

14 showers. Our longest stretch between showers was 8 days, and our shortest stretch between showers was 5 hours.

8 times unintentionally above waist deep in water

1 flipped boat

1 instance of stepping out and there was no ground

1 instance of stepping out into quicksand

5 bail-outs learning to stand up in boat while paddling

Upwards of 500 Mission First Tortillas and likely 10 pounds of pepperoni.

15 campfires

7 pairs of lost or destroyed sunglasses

For anyone who likes graphs (and who doesn’t like graphs?), here’s a tiny bit of data analysis:

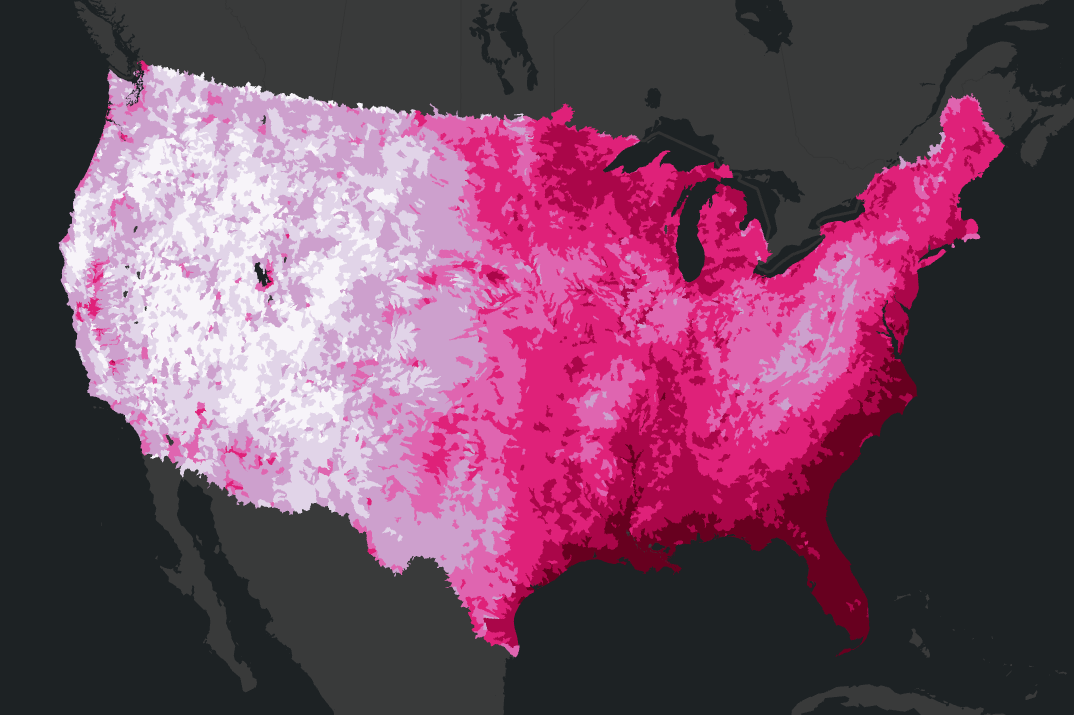

Boborometer

The boborometer is what happens when you admire an 18th-century scientist a little too much and also have access to the paint chip selection of Home Depot. Modeled after Horace-Bénédict de Saussure’s cyanometer—a ring used to measure the blueness of the sky, and, by extension, its moisture—the boborometer replaces noble sky hues with the earthier palette of river sludge. The name comes from the Greek βόρβορος, meaning “mire” or “filth,” and it does live up to both. Technically it was meant to gauge turbidity, but the sun and water kept interfering, so I pivoted to comparing riverbank mud tones instead. It turns out there are more shades of Mississippi brown than any paint catalog dares admit.

On Conflict

S.M.

Our goals for the trip weren’t really in opposition, though it sometimes felt like they were. Leah wanted to paddle the whole river and end the trip as friends1. I never doubted either outcome and instead focused on soaking up enough sunshine to survive corporate law. (Mission accomplished by Minnesota2.)

I did not expect to argue at all on this trip. Blame my youthful optimism and naivety! Leah, ever the realist, disagreed. Two months, in close quarters, under stress, with no breaks? Of course we’d fight.

She was right.

Our disagreements generally arose from two areas:

1) unilateral attempts at optimization and

2) lack of consensus regarding how and when we’d complete the trip3.

Exacerbated by environmental stressors, disrupted routines, and distance from our support networks, these disagreements turned into actual fights. Fighting for us looks like loooong silences leading up to carefully phrased statements of personal opinion, unwillingness to budge from said positions, wondering if we’re terrible people, tears, melodramatic fear that the friendship is OVER, and uncertainty over what we actually agreed to, if anything.

L.P.

After the first week of fighting, I asked if I could share about them on the blog. I wanted this blog to reflect what really happened on our trip, both to jog my own memory later, but also so as not to provide a curated and gilded account to other paddlers or prospective paddlers. I don’t want anyone to look at our blog, and think, “wow, everything went so smoothly for them - what am I doing wrong?”.

I fully believed that we could work through this over the course of 2 months - after all, we’ve known each other almost 15 years through multiple major life events and long periods apart- we weren’t going to suddenly not be friends; this relationship was too important to each of us. At the same time, I knew it was going to get worse before it got better- so much of our early conflict seemed to me to be rooted in miscommunication and assumptions grounded in our vastly different worldviews. It was going to take some time to even start speaking the same language.

I wanted to document that trajectory - to have a platform to say that not all fighting is bad and that not all progress is linear, and also yes, I have fights. Interpersonal conflict resolution isn’t talked about enough. Full Stop. And too often just the idea of having to resolve these types of conflicts leaves people feeling alone, hopeless, and unsure if it’s worth it. There were points on this trip when I felt hopeless too, and I started to doubt my conviction that our friendship was strong enough to bear the weight of public scrutiny on top of everything else. Who was I to think that this would be a success story? What if my pride and desire to make a point pushed us over a line I could not yet see?

But even just in those doubts we can see evidence of fight type #1: unilateral attempts at optimization: what I thought, my pride, line I couldn’t see.

I couldn’t fix this - we had to.

S.M.

Neither of us gives up easily. And so, we began to debrief after each argument, to name what actually happened instead of what we thought happened. We talked about how we felt and how we wanted to feel the next time we disagreed.

Over time, we got better at it. Some of the practices that helped us navigate our disagreements were to ask questions early, to accept peace offerings, to let stress stay where it belongs, and to remember how each person prefers to be cared for. We found comfort in reminding ourselves that we were still friends, despite whatever decision point we faced. We began to avoid absolute and accusatory statements. Our shared emotional dictionary grew to guide us through each conflict. If we felt a fight coming on, we could lean on key phrases to diffuse the tension:

“I notice…”

“When you said that, I heard…”

“You just did … and now I feel …”

“I am going to do this because …”

L.P.

I don’t get mad very much. I mean, sure I can get frustrated, annoyed, exasperated, but it very very rarely escalates beyond minor inconvenience. It’s something we talked about several times during the trip, because it’s sometimes hard to read my expression, so a silence that really means, “I moved on and am now thinking about the way the light bounces off those cliffs” could be misread as, “I am angry about a comment or action from whatever we were talking about before”.

When I was a kid (10-11ish?) it took very little to set me off - a restaurant being too loud could trigger tears, personal attacks, and shouting. We tried stress balls (I threw them at things), tearing up paper in increasingly thick layers (trying to tear through 8 layers at once and failing just made me more mad4), grounding exercises (5 things you can see, etc - couldn’t remember them on my own and wasn’t in a mood to take orders), distractions (I got madder because I felt invalidated/ignored) and probably other techniques that I’ve since forgotten.

What finally worked for me was just gathering up the emotions and putting them in a box. I could be mad later, I told myself, after I faked everyone else into thinking I had calmed down. They wouldn’t know what hit ‘em5. That was the plan anyway. The blessing in disguise is that the box I had wasn’t some hermetically sealed bottle, it was just a regular ol’ leaky box.

The emotions didn’t stay put, like I expected them to, and when I came back to them later, there were less than when I first put them in - a manageable amount, something I could work through rather than unleash upon the world. Over time, I came to rely on my leaky box to leak - dumping my anger there while I sorted out the situation, not making absolute statements or impulsive decisions until the box was empty, and trusting that it would be…eventually. It was never as satisfying as the more immediate ways to dispel my anger, but it worked. Only the big things stay in the box when I come back to check on it, and those can be tackled one at a time.

In our fight debriefs, why I didn’t remember a particular slight or why I didn’t think it had started the night before (it’s always the night before) could often be explained with two words: leaky box.

S.M.

If you can’t tell by now, Leah’s not exactly conflict adverse. In contrast, I hate fighting. I try to avoid it at all costs, keep it secret when it happens, and forget that it ever happened once resolved. But two months of trial and error, tracking, and debriefing have shifted my perspective on conflict. I used to think fighting meant something was wrong. Now, I think it means you care enough to say what you need. To stay in the conversation, even when it’s hard to. You only fight with someone when the outcome still matters — when you want the shared thing to survive, even if it changes shape in the process. Fighting means you’re invested enough to disagree, to ask for better, to keep talking.

Two months on the river will test any friendship. When we started logging our arguments in the blue journal, I hoped the data might explain them. It didn’t. The dots refused to line up neatly. There’s no neat correlation between mileage, weather, showers or stress. What it shows instead is that we kept trying. It’s evidence that affection can survive friction—and maybe even grow from it. Turns out the trick isn’t avoiding conflict— it’s learning to keep paddling despite it.

And, after Alli joined the team, “not ditch the dog”.

Though the Louisiana rain threatened to undo it

And what completion really meant

I mean, come on - it’s just paper - it shouldn’t be that hard

They didn’t know what hit them the first time either, but that’s beside the point

This is truly fascinating and I am so grateful that both of you were willing to share so much and so deeply. You set a true example for how others can build and maintain their relationships under harsh and stressful, and amazing, circumstances!

I am still in awe of what you two young ladies have accomplished. Reading about how you two managed to deal with “disagreements” touched me. At my age you would think interacting with others wouldn’t ever be hard. But I have found that is not true, even when it’s with those you love. Thank you for sharing and giving me a new prospective on “differences” of opinions. Most of all, thank you for the huge contribution you are making to feeding those in need in central Mississippi. We can never say “Thank You” enough.